|

| Lyle Mays : Eberhard Self Produced |

During his closing days, Mays devoted himself to honing, polishing, and completing a musical project that had consumed him over the years, a recordable dedication to one of his early inspirations, the progressive double bassist Eberhard Weber. Mays first started playing the armature of this composition back in 2009 at a festival in his home state of Wisconsin. The German bassist had suffered a stroke in 2007, and so Mays’ first public performance of this piece was as much a healing, a musical encouragement to Weber to recover, as it was a homage to the man, his work, and its influence. Sadly, Weber’s medical setback was more permanent than originally hoped for. The now eighty-one-year-old bassist has never played again.

Mays came to national prominence for his work as the collaborator and co-composer of the Pat Metheny Group. During that period Mays always left his unmistakable imprimatur on some of the group’s most endearing records. The artist won ten Grammy Awards and was nominated twenty-three times over the years. Despite his importance to the success of the PMG, Mays was satisfied to work his musical and technological magic, mostly avoid the spotlight and be satisfied to play the sidekick to Metheny, his Doc Holiday to Pat’s Wyatt Earp at their musical OK Corral. Throughout his life he was always fascinated with technology, chess, architecture and mu

Mays was playing piano and organ from a young age. He attended North Texas State University (later University of North Texas) and won his first nomination as the composer/arranger for his work on the album Lab ’75 with the school’s One O’clock Lab Band.

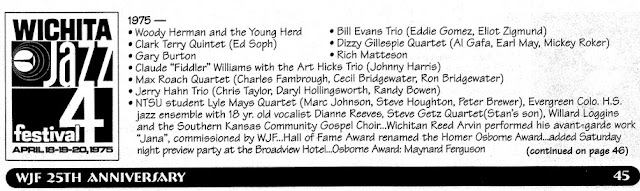

While still a student, Mays performed at the Wichita Jazz Festival in 1975 and it is interesting to look at the festival’s performer list from that year as this event proved to be pivotal to Mays' future career. Exploring a musician’s trajectory is always of interest and timely intersections with other musicians often lead to life-changing paths.

From WJF 25 years of Great Jazz Compilation by Gary Hess

Mays’ Student Quartet included bassist Marc Johnson, drummer Steve Houghton, and woodwind player Pete Brewer.

It was unpredictable the way new connections casually made at venues like the WJF could be so important to a young musician’s future. For the bassist, Marc Johnson stars somehow cross each other’s paths and the festival likely served as an informal entre to the pianist Bill Evans. Johnson was eventually chosen to replace a departing Gomez in Evans’ last trio with drummer Joe LaBarbera, and he did so from 1978 until Evans’ death in 1980. No doubt a life-changing experience for the bassist. Johnson went on to a stellar career as one of jazz’s most respected bassists. He remained associated with his classmate Mays for years with his sonorous double bass heard on six of the keyboardist’s recordings as a leader including The Ludwigsburg Concert from 2015.

Drummer Steve Houghton continued his career as a respected sideman, eventually turning to academia, becoming a respected associate professor of percussion at Indiana University among other institutions. Woodwind artist Pete Brewer would continue his career as a successful freelance musician.

If you look at the artist roster for the 1975 Wichita Jazz Festival, the lineup had s a plethora of great drummers that included Max Roach, Ed Soph, Mickey Roker, and Bob Moses (with Burton), but you will also see other important acts including Woody Herman’s Young Herd, Bill Evans Trio, and Gary Burton’s group which included the young guitarist, Pat Metheny. Woody Herman, the legendary bandleader, and clarinetist must have liked what he saw of the Lyle Mays Quartet in Wichita. Shortly thereafter Mays, Brewer, and Houghton were recruited to become new members of Herman’s traveling Thundering Herd later in 1975. Mays was to be the keyboardist for Herman for eight months into 1976 until another Wichita twist of fate would change his path again. Mays and the Metheny first met at the Wichita festival in 1975. They mutually found that they had musically compatible goals. Metheny would leave Burton and Mays left Herman and the two decided to start a new group. The group would record and release their first collaboration Watercolors in 1977 under Metheny’s name. The collaboration would be a rich one and it would last for most of twenty-eight years through their last recording together as the Pat Metheny Group This Way Up in 2005. By that time, traveling and presumably, health issues induced Mays to call it quits.

Watercolors ECM 1977

Watercolors would be Mays' first opportunity to work with the progressive European bassist Eberhard Weber. Metheny had worked with Weber while he was with vibraphonist Gary Burton on his albums Ring from 1974 and Passengers from 1976. Mays again played with Weber on the bassist’s album Later That Evening from 1982. There is little doubt that the German’s playing influenced both these young American pioneers.

Despite being strongly influenced by his classical training, a musical history that he shared with Mays, Weber created his own minimalist, ostinato-based, ethereal, and melancholic approach to his work. He was most likely influenced by the avant-garde composers Steve Reich and Terry Riley. By the early seventies, Weber designed and preferred a five-string-electric bass that extended the instrument’s range, adding more depth and drama to his playing. He was never a boisterous performer who commanded attention. Instead, he wanted his music to speak for itself. Like the free-jazz movement that went off in one direction that veered away from traditional hard bop jazz, or even the frenetic fusion of the early seventies, Weber’s music was a detour that embraced a gentler, more thoughtful approach. There is no doubt Weber’s musical approach, almost chamber-like, was a serious signpost that caught Mays’ attention.

Eberhard is a thirteen-minute opus of pure Mays’ magic. It is a splendid piece of mostly through-composed music. Mays explores elements of classical, jazz, chamber, minimalism, vocalization, and cinematic musical qualities. Typical of Mays’ work, the piece has a tonal depth and emotional reach that displays the man’s expansive concept of what music should be. While the work is a homage to Weber, the music is pure Mays.

Mallett artist Wade Culbreath opens the piece with a repeating tonal movement that creates an almost other-worldly atmosphere upon which Mays solemn pianistic probing floats. Jimmy Johnson’s electric bass bellows beautifully with authority and poignancy in what I have read is a fully composed part. Mays’ niece, the vocalist Aubrey Johnson, enters the scene with a feathery vocalization that has angelic elements as she vocally traces the music lines emphatically. At one point, Mays’ piano has a very bluesy crossed with Americana feel to it that has always been part of his style. Steve Rodby’s beautiful double bass anchors the time with its fluid bottom tone. Bob Sheppard’s flute is introduced for another tonal factor that adds to the orchestration along with some electronic synthesizing effects that seem to be a identifiable part of Mays’ signature style. A quartet of cellos seamlessly adds to the pallet of tonal possibilities. Mallett, piano, flute, bass, and drum interact swelling with energy, and Bill Frisell’s twangy guitar voice briefly makes its appearance. The separate voices of Johnson and Rosana and Gary Eckert almost conjoin. They meld like three pieces of gold transforming into one brilliant ingot by the heat of a scorching crucible that is Mays' music. Jimmy Branly’s drum work erupts like percolating lava, and Alex Acuna adds perceptive percussive accents that just increase the temperature of the rhythmic brew that Mays compositionally constructs. Culbreath and Johnson beautifully match each other’s notes like two empathetic savants. Mays introduces a jazz septet that gets into a fiery vibe section that is the apex of the piece. The section includes some perceptive organ work by Mitchel Forman, with Mays on piano, the explosive Branly on drums, subtle Acuna on percussion, Steve Rodby’s strong acoustic bass, and the multi-reed master Bob Sheppard’s tenor saxophone.

Sheppard’s improvised solo runs for a little over two and half minutes and starts at about the 8:24 minute mark. It is a masterwork of controlled passion powered by a internal sweltering fire that he can call on at any time as is needed. Mays’ orchestrates the music to the summit and then allows Culbreath’s gorgeous, resonant mallet work and some of his own synth accents to melt the piece away, like a fading crimson sunset, turns the sky into a brilliant pastel haze.

The more I listen to this, the more I aurally observe the nuances of his orchestration, the more I realize how much we will miss Lyle Mays and his beautiful world of sonic colors. Eberhard could certainly be positioned as Lyle Mays epitaph, his crown jewel, but while it certainly is his last recorded work, I am sure that Mr. Weber will listen to this piece, love it and it will certainly put a bittersweet smile on his face. This work should excite those of us who have loved Mays'work for so long, to go back and revisit the body of this exceptional artist's life work. If we do this, we will undoubtedly honor this man’s legacy in the fashion he intended it to be listened to, with joy.

No comments:

Post a Comment