|

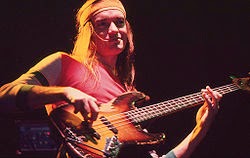

| Richard Davis |

Richard Davis has always followed his muse throughout his career. A world class bassist, an avid horseman, a respected educator a socially conscious activist.

Whether it be as an accomplished studio musician on mainstream albums by the likes of Barbara Streisand or as a pivotal driving force on a seminal album by Van Morrison or the rock steady bassist behind in inimitable Ms. Sarah Vaughan, Davis has always left his mark. As an important member of the progressive ensembles of Eric Dolphy, Andrew Hill, Sun Rah and Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Davis has always let his music speak for itself. People noticed.

His ability as a classically trained bassist, had at one time, inspired a younger Davis to pursue a symphonic career. Racism often reared its ugly head and he was repeatedly rejected by the firmly entrenched white establishment that dominated the symphony scene in the fifties, sixties and seventies. He was often times not given the courtesy of a call back, even when it was obvious that he was the most accomplished of the contestants applying for the position. Undeterred, the talented Davis could not be denied, eventually playing with such classical luminaries as Leonard Bernstein, Gunther Schuller and Igor Stravinsky. Cream inevitably rises to the top.

Leaving the established jazz community in New York in 1977, where he was a respected member,Richard Davis's career took another turn, this time assuming the role of educator and mentor as a professor of classical bass at the University of Wisconsin, where he still teaches. Along the way Davis has made some beautiful music and inspired scores of aspiring musicians. Despite his generous spirit and stated goal to pass on his accumulated knowledge to the next generation, Davis, as a Black man in a predominantly white state, has seen and felt firsthand the ugly effects of racism, even in the bucolic setting of the University of Wisconsin in Madison where he lives. Undaunted by a lifetime of racially motivated slights, both real and perceived, Davis steadfastly maintains a surprisingly positive attitude and believes in sowing the seeds of racial harmony and acceptance. He supports education about racism and its roots and is hopeful that with open conversation between the races, we can come together in harmony.

As a musician and educator he has formed the Richard Davis Foundation for Young Bassists, which promotes educating students on the bass at an early age. As an activist Davis, formed the Retention Action Program (R.A.P.), an organization dedicated to increasing the retention levels for students of color at U of W. He is also President of the Madison Wisconsin Institute for Racial Healing, an organization dedicated to understanding the history and pathology of racism, with the goal of hoping to heal racism in individuals, communities, and institutions both in Wisconsin and throughout the USA. So it was of great interest to speak to Mr. Davis about his experiences and listen to some of his philosophies about racism and how we can educate ourselves to prevent its continued proliferation to the next generation.

NOJ: Let’s

get some of your views on the state of race relations in this country. In the

nineteen sixties do you think you took a militant stance against racism?

RD: No I didn't take a militant stance, because militancy defeats the purpose. I didn't take any particular stand, I just thought it was something that I didn't like. I didn't go parading around.

NOJ: You

have been an educator at University of Wisconsin in Madison since 1977. What

made you leave New York?

RD: I just

decided that I wanted to start teaching some younger people what I had learned.

NOJ: How

did you find Wisconsin?

RD: Cold.

NOJ: Were

the people of Wisconsin receptive to you as a Black educator in a relatively

predominantly White state?

RD:

Wisconsin has a reputation for being a racial state. I think … some people

feared me because I was Black. They thought I was aloof, but I had to protect

myself….Wisconsin is very racist.

NOJ: I take

it you were a bit of a pioneer there?

RD: What do

mean by a pioneer?

NOJ:

Somebody that went ahead of other people and blazed the way. I take it by now

there is much more diversity and integration in the school system?

RD: It’s

still the same, nothing has changed.

NOJ: Well,

that’s disheartening.

RD: I’m

still working on diversity. I have some allies. I have lots of allies and I

have a lot of people who don’t even realize that it exists there.

NOJ: Has

affirmative action helped Wisconsin integrate more people of color into the

educational system?

RD: When

you look at the numbers there is still 3% Black and 8 % people of

color and I don’t know what they are doing about that.

NOJ: You

are now 84 years young. You have won numerous awards and accolades throughout

your career including the nation’s highest honor the NEA Jazz Masters

Fellowship Award just this year. You have formed the Richard Davis Foundation

for Young Bassists, The Retention Action Project (RAP), and SEED (Seeking Educational

Equity and Diversity) all reach out programs that inspire harmony and love. You've said you wanted to live to be 137 in order to do the things you still

want to accomplish. What are some of those things that you feel remain undone

for you?

RD: Well I

think that going on a global quest will influence every part of your life. I

talk about the oneness of humankind, the fact that we all come out of the same

womb of an African woman. Only one tenth of one percent (of our genetic makeup)

accounts of the difference is our skin color.*

* "If you ask what percentage of your genes is reflected in your external appearance, the basis by which we talk about race, the answer seems to be in the range of .01 percent," said Dr. Harold P. Freeman, the chief executive, president and director of surgery at North General Hospital in Manhattan, who has studied the issue of biology and race. "This is a very, very minimal reflection of your genetic makeup," Quote from a New York Times article August 2000, entitled "Do Races Differ, Not Really, Genes Show" by Natalie Angier.

Somewhere

along the way it has been forgotten and we see each other with different skin

instead of looking at each other as ourselves; one person, one human being.

That theory, if it is practiced and gets a resurgence of the truth, it will

cease a lot of problems. Like that shooting in Ferguson, MO. That’s because the

police are afraid of Black people and Black people are afraid of White people.

It comes from fear and ignorance. If we can gt past that fear factor and that

ignorance factor we will make tremendous strides. You see, this country is

not built on equalization for everybody.

It is built on that fact that some of the White people are oppressors

and the Black people are being oppressed by this attitude. A White kid gets

treated different then a Black kid. Have you ever heard of a White kid being

shot down by the police? So it is just a matter of equal treatment of each

other and this will all go away.

NOJ: Do you think both sides can reconcile their

differences?

RD: Sure I

think so, especially if there is enough going on and if people gather and talk

to each other. Most of all White people have to talk to White people; Black

people talking to White people is a good thing, but they have to start talking

to each other. The police department already has an impression of what they are

faced with when they see Black people. If you have five Black people standing

on the corner talking, Police come by and they think something bad is going to

happen. If they see five White people standing on the corner, they think

nothing of it. That has got to change.

NOJ: It’s

unfortunate but historical experience can sometimes create stereotypes that can

be dangerously wrong. What has happened before is hard to erase from people’s

minds and once established it is hard to break impressions and habits.

RD: Well I

call it (being) emotionally attached. That is why some people are still singing

the “Star Spangled Banner,” where so much of that is not true. They are singing

“the home of the brave and the land of the free.” People are singing that with fervor.

Everybody is not free, but they continue to sing it.

NOJ : There

is a national pride and sometimes people wrap themselves around the flag for

the wrong reasons, but I would prefer that people believe in their country than

not. Sometimes that belief is not validated by actions. There will always be

things that are wrong in this country, but do you just stop people from showing

some amount of patriotism?

RD: Well I

am not a patriot. I am not a patriot because the country does not look at me in

a way that they look at (White people.)

An American is not me; an American is a White person. When you talk

about a Black person they are treated different. …I will be an American when I

am treated like an American. But that …”land of the free and home of the brave,”

wait a minute, let’s really look at the truth with intelligence, to see if it

is true where we can continue to tout those things. I don’t consider myself an

American, because I am not treated like a White person, an American is a White

person.

NOJ: If you

are not an American than what do you feel you are?

RD: I am an

African-American misplaced in a land that does not accept me on the basis of

my race.

NOJ: Well

that is upsetting to me as a person who would hope by this time we have made

our way to acceptance and inclusion and have made more progress than that.

RD: Well there

should be more people like you who exercise that (sentiment.) If a Black kid in school if he does something

wrong they suspend him and take him to the Principal’s office. If a White kid

does the same thing they just slap him on his wrist. So it is not a fair

representation of saying we treat everybody with equal respect. Did you see the

show Democracy Now. You should go to www.democracynow.org and look for the

edition for August 19, 2014 and you will see a man named John Powell. He will

explain this so well. He elaborates very elegantly on what I just told you.

NOJ:I’d be

interested in knowing as a Black man in this country who has been around for

many decades, what do you think of the current President and how effective he

has been?

RD: I don’t

get into politics that much. I know he is in a position that is very sensitive

because he has to speak for White and Black people. He can’t show favor for one

or the other and he is somebody who is in that position. It is not the Office

of Dignity that is going to change anything.

He could be the President of the World; it is the individual person,

walk around everyday life person who is the one subjected to this and the only

one who can change it.

NOJ: With

all the evil that seems to be cropping up all over the World. Do you believe

music and specifically jazz music can be an answer to some of the problems that

we have in communicating with each other across sectarian, racial and ethnic

lines? Do you see music as a vehicle that can bridge this gap?

RD:

Basically speaking, no. There has been a lot of jazz recorded, there have been

a lot of protest songs recorded talking about race, but have things changed?

You might get a few converts, because of what you are saying, but not enough to

make an overall general big change. It won’t come from one entity; it has to

come from the heart of the person. Even

with the laws that they they have in place, that doesn’t change anything, it has to

come from the heart of the person. I have many White associates who would say

the same things that I just said who are making a difference, and (they are) mostly

females!

NOJ: How does that heart get changed, how do you

think that change can come about? Is activism the answer?

RD:

First you have to be educated to a high level of education. I have tons of

books in my house, most of them written by White people, who are anti-racist. I

go to conferences where all these people gather together and try to discuss

these things and then take it back to their homes and try to promote an

attitude. Some of the teachers, who are white and want to go to these

conferences, they ask their administrators for the money to go and some

administrators will say that is a good

thing we will give you the money and some say what is the use of all that? It’s been like

that for four or five hundred years.

NOJ:

Do you think that the races will eventually undergo miscegenation to the point

that it doesn't really matter anymore?

RD:

it’s happening now. The minorities that they talked about in the last decade

are no longer the minorities; they are the majority in some cases. People don’t

use that word minority anymore because there is more Hispanic growth that is

making them change. That is frightening some White people because they see

themselves as not the majority anymore. The whole thing is a transformation of

attitudes and that takes a long haul.

NOJ:

So the answer is time. Time equalizes everything.

RD:

Well used time. See, the education system is racist, the prison system is

racist, the judicial courts are racist, the Religions are racist, so you have a

whole system of institutionalized racism that has to be readdressed and

reassessed. There are more Black people in jail then Whites. There are teachers

who don’t regard their Black students as well as they regard their White

students. So the whole thing has capitalized on organized institutional racism.

NOJ: Do you think that if there was more economic equality and opportunity in the

country that the differences in the races wouldn't be as exacerbated?

RD:

Well economics is a good part of the problem, because it gets to be classicism not racism. How many Black people are making the same amount of money that an

ordinary White person is making? I must say that impoverished people are just not

Black people either; there are many White people that are very impoverished. But

their skin color gives them an advantage, even their names gives them an

advantage. You see many violations on the scene where racism crosses over to

classicism. A middle class White teacher teaching Black kids-first of all she is

afraid of them, she is not going to hang out with them, accept anything that they

say as worth anything, she won’t even call on them when they raise their hands

( In class).

NOJ: How-if you have a young White, woman teacher, who is working in a predominantly Black

school, and she fears for herself and her safety- how do you overcome that embedded fear?

RD:

First of all that is a lot to overcome, because (in many cases) all of her life

she was never subjected to knowing about a culture other than her own. So she

was involved with people who look like her, think like her, act like her and

she has, what you might call, a shell around her existence in relation to other

people. Even when college students come here from neighboring towns around

Madison, some of them have never been around people of color. So they come in

here with their naiveté and their non-exposure, looking at Black people and

they are afraid of them and consequently they react to them as if they are

their enemies. I will give you an example; a White woman gets on the elevator

at the University, the elevator stops, and a Black man gets into the elevator

and she starts screaming. The police come and they say “What has he done to

you, mam?” and she says “He startled me.”

NOJ:

That is just sad.

RD:

Well it shows that her experience with a person of another color is fear. She

heard they were going to do something to her. A White woman worked for me for

three years at the campus. One day she came to my office and started crying. I

said “What’s wrong with you?” She said “Well my mother told me that if I was

ever going to be in a small room with a Black person I would be raped.” Now this woman had been working with me for

three years and all that time I would give her work and we would be in a small

room. Now for all that time she struggled thinking, “He is going to rape me one

of these days,” and she wanted to tell her mother that she had scarred her mind

with this concept. That is what it is; the parents perpetuate a racist

attitude. I have seen White women clutch their purses when I go near them, or

standing in line behind them, they will clutch their purses.

NOJ:I guess it is hard to relate to this as a White person.

RD:

We just don’t know each other. I live in a very plush house; it is on the South

Side of Madison, lakefront and I am the only Black person in this neighborhood.

Now, there are White teachers in the public (school) system in a town that is

only ten minutes away from here, that will not go into the supermarket that I

go into, because they are afraid. My girlfriend is White and I asked her, when

she goes into this market how many people does she see that are Black? She says

“maybe about three.” It was all White

people that went to this store. So these teachers perpetuate racism by telling

their friends “don’t go onto the South Side of Madison because something will

happen to you.” I live on the South Side. I have been here since 1987, but they

are afraid to go and they have never even been here.

An

Administrator from the University, when they built a new building on the

dividing line between North and South (Madison), she asked me “What should I

do?” I knew what she was implying; now she was going to be going to work on the

South side. I said Get your laptop and your chair with wheels on it and roll on

down to the South Side with it.”

Things

are changing on the South Side now because gentrification is coming in. They

are building a lot of plush apartment buildings and other things. Then those

White people will feel better about coming on the South Side, because more

people that look like them are coming. The Black people in the neighborhood,

some of them will have to move out, because they can’t afford it anymore. It is

all around me where I am living. Now they have a Dunkin’ Donuts here… and tall

buildings and hospitals, it’s gentrification and it will change the attitude of

people being afraid to come here. I have never been to my neighborhood

supermarket where I see more Black people than White people, but people who

don’t live here think there are only Black people going in there.

NOJ:

I hope things will change and I would like to believe that we are better than

that and strive to be better and be open.

I agree with you that it has to start with us. It has to start with us

teaching inclusion to our children and then they doing the same with their

children.

RD:

I always say, you know how people put pictures up on their refrigerator? Well

put some Black people up there. (Laughter)

NOJ: I really appreciate your time Richard. I am

sure the readers will enjoy the conversation. Thank you.