|

| Randy Brecker photo credit Francisco Molina Reyes II |

NOJ: Let's start with the obligatory biographical questions. You grew up in Philly in a musical family. What first

inspired you to pick up the trumpet?

RB: Like you said, it was a musical family and we grew up in

Philadelphia and that was a real trumpet town back then. In a way it still is.

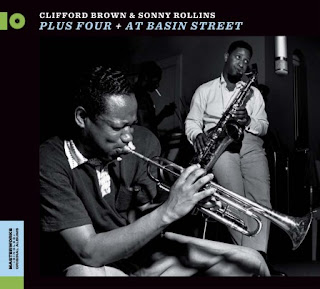

A lot of great players come from there. During the early fifties Clifford Brown

was around. My father loved him and he had all his records and went to hear

him. He also knew Dizzy kind of well so he had Dizzy Gillespie records, Miles

Davis, Chet Baker, he was a big fan.

NOJ: Did your father actual play piano with these guys?

RB: I don’t think so. I’m not sure how he met Dizzy or what

that relationship was, I was so young at the time. He was partners in the first

Theater in the Round Tents that started there. There were three tents and on

the off nights they always had jazz concerts so that might have had something

to do with it. I remember I heard Dave Brubeck there, there was three tents and

the stage revolved. They also had like Broadway style shows.

My dad was a great player and he did have jam sessions at

the house all the time with some good Philly players. Once Jon Hendricks from

Lambert., Hendricks and Ross came over, he was snowed in. The level of

musicianship at the jam sessions was pretty high for the most part. As a kid I

fell in love with the trumpet. The thing that set it in the third grade, we

didn’t have the greatest music program, and they only had trumpets or

clarinets. So I grabbed the trumpet, I was actually looking at the trombones

because they looked a little bit more fun to play when you are eight years old,

but I got the trumpet. I ended up with a horn and here it is sixty-two years

later and I am still trying to figure it out.

NOJ: I heard you mention in another interview that your

father played a little like Dave Brubeck, which leads me to my next question.

Why do you think that for all his popularity Brubeck’s piano style was not

emulated by the up and coming players as much as say Bill Evans or McCoy

Tyner’s style?

RB: That’s a good question. It was a unique band. When you

think of the classic quartet it’s hard to separate Dave from the rest of the

band with Paul Desmond, Joe Morello and Eugene Wright, especially in their

prime, so maybe that has something to do with it. It’s true he is more known as

a composer. Miles was a fan of his compositions and did some of them. I think

he was so tightly tied up into the group sound that when you think of Dave

Brubeck you think of the whole thing, as opposed to him separately. His way of

improvising was also tightly involved in that group so you can barely think of

him outside of that group. My father was a big fan and if anybody sounded like

Dave Brubeck he did.

NOJ: You attended school at Indiana University. Was that

your first choice for university education and if so why?

RB: Well I went there when I was fifteen, to the Stan Kenton

band camp for two weeks. It was one of the instigators that led me to me

wanting to be a professional musician. My instructor was the great Marvin Stamm

whom I became friendly with. Subsequently I have done a million dates with

him. He became close to a young Peter

Erskine who was six or seven years old, could barely touch the pedal and was

playing great. Marvin was friendly with Peter’s older sister; Peter’s father

was the camp Doctor. I was standing on the curb after the two-weeks of camp,

watching Marvin get on the bus with the Stan Kenton tour, about to leave and

Peter’s sister was on the curbing crying and waving goodbye. So I thought to

myself this is what I want to do, when I grow up. I’ll never forget the look on

Marvin’s face as was pulling away. (Laughing).

|

| Louis Hayes and a young Peter Erskine at the Stan Kenton Jazz Camp 1961 (photo courtesy of Peter Erskine's photo gallery) |

There were some great musicians

there at the camp. Cannonball Adderley’s Sextet was there with Nat Adderley, Joe Zawinul, Sam Jones and Yusef Lateef , Donald Byrd was also there, it was incredible. We got to pal around

with these guys. I also met Dave Sanborn, Don Grolnick, who else was there; Keith

Jarrett was there although he didn’t talk to anybody, Lou Marini so guys who I

have maintained relationships with for years. Jamie Aebersold was a little

older but he was also there. This was at the Indiana University Music School which was brand new; a round, very modern looking building. They were in

the process of building up their music department to be a world class program.

They had a big endowment, a lot of benefactors; so they were getting people

from New York to get out there and teach. By the time I was ready to pick a college,

they had established themselves as one of the greatest music schools in the

country. They had a great trumpet teacher named Bill Adam who went on to also

teach Jerry Hey, Chris Botti, Larry Hall, Charley Davis. I can’t remember if

it was my first choice, but it was up there and I knew the place, I knew some

other guys who were going, so I ended up going there.

NOJ: You went there for three years and then later finished

up your degree at NYU is that right?

RB: Well what happened was the band at IU was fantastic. We

had particularly great playing band. I was in and out of the music school, I

must say I had a kind of sketchy education. I was in music education for a

while, but I didn’t think I wanted to teach. I liked to write papers, so I was

in liberal arts for a while. I wrote stories and I was in Communications, radio

and TV and floating around. I always maintained my trumpet lessons with Bill

Adam and I was studying with the great Dave Baker in Indianapolis every week and

I played in the I U big band.

NOJ: Now Dave Baker is a trombone player right?

RB: Yeah he was a trombone player who played with George

Russell. It’s funny the ABC’s of jazz education were all at I U. Jamey Aebersold,

Dave Baker and Jerry Coker. I U was also ahead of its time as far as jazz

education and those guys became really well known as jazz educators. As far as

that went I was at the right place at the right time.

Our band won the Notre Dame Jazz Festival in 1965. Everyone

shot for that prize. It was like the Olympics of Big Band competition in the

country and we won hands down that year. Clark Terry gave me an award for

soloist and one of the rewards was the band was offered a four-month State

Department sponsored tour of the Middle East in 1966. So I went back to IU for

a semester and then didn’t go back my last semester and instead we went on this

tour through all the Middle East and India, Pakistan, Ceylon (now called Sri

Lanka); fascinating trip.

|

| http://waxidermy.com/indiana-univ/ |

That summer there was an international jazz competition that

we saw advertised in Downbeat when we

were in India and it was to be held in Vienna, Austria. So some of us decided

to make our way to Vienna to try out for the competition. Gary Campbell, a now

established musical educator and great saxophonist and I went to Vienna. The

judges were Art Farmer, Cannonball Adderley, JJ Johnson, Joe Zawinul, Ron

Carter and Mel Lewis and it was held together by a wonderful Viennese jazz/classical

pianist named Friedrich Gulda. I won an award at that festival, but all the

contestants were bunked together in a youth hostel and that was a blast. We

were all young kids 18, 19 or 20 and the group included Jan Hammer, who at the

time played like Wynton Kelly, George Mraz, Miroslav Vitous, Claudio Roditi, Jiggs

Whigham, Franco Ambrosetti, Joachim Kuhn

and Tomaz Stanko, who now lives in NY. Man

it was an amazing vignette. I had a band back there with Jan Hammer and George

Mraz, we were the second place winners.

To get back to your question, I came

back to New York and studied with a great trumpet player named Ray Crisara, but

there was a lot of work around. Mel asked me to join the Thad and Mel Band.

Clark Terry was starting a big band he asked me to join that too. Marvin came

back into town coincidentally and he introduced me to some studio

work. So I kind of got sucked into to all this work as soon as I came to town.

I was really lucky, in the right place at the right time. In a nutshell that’s

how I ended up in New York.

NOJ: That was September of 1966. This was during the Vietnam

war and there were protestors in full swing. Did that affect your decision to

go on this State Department sponsored tour?

RB: Well, we really wanted to do this and I think at the

time we mended a lot of fences although at the time it may have been

controversial to some I suppose. We made a lot of friends on that trip.

Subsequently I did a couple of other State Department tours to the communist

countries in 1989 about six months before they all fell like dominoes. It just

mended a lot of fences. People loved the music and the band. We saw all this

stuff happening over there. We ended up on a lot of Army bases. At one point I even

thought of making that a career playing in an Army band.

Getting back to that original tour in 1966, I still have a

lot of pictures from that trip and we just had our fiftieth anniversary reunion

of that tour this past May. A lot of the guys are now established educators and

imagine this we had a jam session at one of the clubs around IU after all these

years. It was a heck of a trip.

NOJ: What was your first break into playing serious jazz and

who gave it to you?

RB: The very first one I remember was Clark calling up and

saying he was starting a big band and would I join. I was just thrilled; I

couldn’t believe it was him on the phone. Subsequently, right around the same

time I went to hear Thad and Mel’s band, which had just started up, and I think

Bill Berry was leaving the band, and Mel asked me to join the group. So imagine

how thrilling that was. Philly was a big R &B town when I was growing up,

a melting pot of different styles of music. So at the same time I was asked to

join Blood Sweat & Tears. So I had my foot into the rock world too. I had

grown up with the music and enjoyed pop, R & B and it was a great horn

section in that band. So all this was

happening at the same time. Oh and Marvin was using me as a sub for studio

work, there was a ton of session work at the time. So it ended it with me being

a studio guy doing a lot of studio work also.

NOJ: So Marvin really got you into the studio work?

RB: Yeah he really helped me a lot. Thad also helped. You

would go to the studio for a jingle and the other trumpet player would be Thad

Jones or Snooky Young. Ernie Royal was still in town. Bernie Glow. It was great

days, great players that took me under their wing. Duke Pearson’s Big Band was

also happening at that time. Marvin helped get in that with Joe Shepley and

Burt Collins. We were known as the “White Knights” in that band. That band

worked quite a bit at the Half Note, as did Clark Terry’s Band. So there I was

as a twenty-year-old kid thrilled to be around all these guys and doing all

this, I never thought I would be doing this in a million years.

|

| Marvin Stamm |

NOJ: You mentioned

Clifford was a big influence from hearing him at home. Who else were your

trumpet role models and why?

RB: Well he was definitely one of them, because we had all

his records. I never got the chance to see him before he died because I was too

young. I was ten years old when he was killed. I remember that day clearly when

my father found out. So he was up there, but also, as I had mentioned, dad

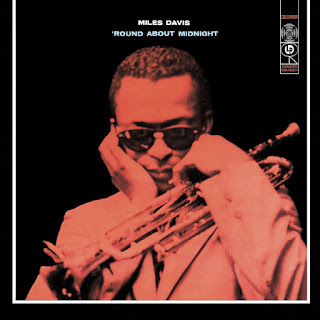

loved Miles. I started to play along with records, and Miles was a little

easier to play along with, and Chet Baker. They were so lyrical and didn’t play

quite as many notes as Clifford and didn’t have as much control of the horn as

Clifford did. So I started with those two when I was ten or eleven. First, a

Miles record came out on Columbia called Round

About Midnight, and I started with ballads. I also had a record by Milt

Jackson called Bags Groove, that was

a great one to play along with. Along with my classical studies I started

taking dad’s records up to my room and just playing along with the records.

NOJ: You came up behind guys like Miles, Clifford was before

you, but Miles was pretty present. Other guys like Woody Shaw, Lee Morgan and

Freddie Hubbard. Give us your take on all these guys and how they affected your

playing?

RB: I suppose Woody was the one I was closest to, because we

were the same age and we met. He was already playing with Horace’s group. I had

been spending the summer- I was maybe nineteen and he was maybe six months

older than I was-in Seattle taking some courses at the University of

Washington, chasing after my first girlfriend, and just spending the summer

there. That was also a life changing summer, there was a lot happening that

summer in Seattle. Larry Coryell was still living there and I played with him.

He had a steady gig at a place called the Embers. There were just a lot of

great musicians in town and there was a club called The Penthouse, that

featured like the old days, a group for a week, but then interspersed jam

sessions with local guys on the band stand. Art Blakey was there for a week

with Lee Morgan. I hadn’t really met Lee before, although we were both from Philadelphia

and we both had the same trumpet teacher. So we got friendly that week. He

invited me to sit in with Art, but he didn’t ask him. I remember they were

playing “A Night in Tunisia” and Lee motioned for me to come up and sit in. I

started to go into a solo and Art looked around and went into a drum solo to

drown me out. (Laughing) He started yelling at Lee saying “I don’t want nobody

sitting in, I told you that.” They had a big argument on the bandstand. The

next week, imagine this, Horace Silver was there with Joe Henderson and Woody

Shaw. Woody had heard me play and was also very complimentary. He sounded just

great and we kind of hung out the whole week at the club.

|

| Woody Shaw |

When I got to New

York, I guess a couple of years later, and I got in touch with him and he was

also very helpful getting me gigs. He also wound up playing in Clark’s band for

a while. So we pal’d around. I was closest to him and we compared notes. Lee

was five years older so I would go hear him play, but I wasn’t that close to

him other than to say hello. Miles was a little older still and I didn’t get to

know him on a personal level until later, when we had our club Seventh Avenue South (a onetime popular

NYC jazz club). He would come down and hangout a lot and say outrageous things

to everybody. So I got to know him pretty well during that period, but this was

late seventies, early eighties.

NOJ: What about Freddie?

|

| Slug's Handbill featuring Jazz Communicataors (courtesy of Frank Mastropolos's BedfordandBowery.com) |

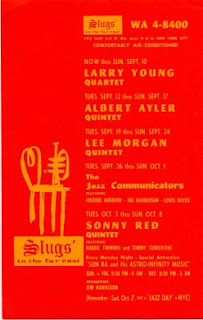

RB: Freddie was also very helpful I must say. Both Woody and

Freddie recommended me to Art Blakey’s band. I played with him off and on for

about a year before Dreams was started. My first night with Art down at Slugs (a downtown now defunct jazz club),

Woody and Freddie were in the front row. I was pretty much of a nervous wreck.

He was also very nice to me when I got to New York and of course he was a big

inspiration. I went to hear him play whenever I could. He had a band with Joe

Henderson, I think they were called Jazz Communicators at Slugs

I was lucky enough to do one extended tour to Japan with

Freddie. Two trumpets, three saxophones-it was Michael Brecker, Joe Henderson

and Joe Farrell- that was the front line can you imagine? It was called the Aurex

Band “D” at the Aurex Jazz Festival. We were the Fusioneers and the rhythm section was George Duke, Alphonso

Johnson, Robben Ford and Peter Erskine. That was when jazz was huge in Japan, we played baseball stadiums, fifty thousand people. We were known as fusion

band “D” that was how the Japanese labeled everyone. That was a wonderful trip

where I got to know Freddie and both Joes pretty well.

NOJ: In 1967 you supposedly answered an ad for horn players

for a band that was to be the original iteration of Blood Sweat '& Tears.

RB: I didn’t quite answer an ad. They called me up. They had

the band set, but one of the trumpet players didn't want to leave town because he had a teaching

gig he didn’t want to give up. So they called me and had heard about me

through the grapevine and so I joined the band.

NOJ: At the time did you really think rock/R'&;B and jazz

could be melded well together and was it an easy transition from straight ahead

jazz?

RB: It was a lot less difficult than you would think,

although jazz and rock was just getting started. I had grown up with rock, I

liked the Beatles, I liked the Stones, I played in a lot of R & B bands in

Philly. Organ trios and blues bands mostly. The gigs were a lot more prevalent

in Philly than the jazz gigs. One of my first gigs in New York, I forget how I

got this one, but I played with an R & B band at the Metropole (a jazz turned strip club on 7th Avenue and 47th

street in NYC) with the Go-go girls. So I got to learn a lot of the repertoire.

I always forget to mention this, but when I went to IU, Booker T was in the

jazz band playing trombone. He was getting a master’s degree in music

composition. So for two years I played around I U with him. We played quite a

bit so I kind of learned all the Stax (Records) stuff.

|

| The Metropole Cafe on 7th & 47th St NYC |

NOJ: How chaotic were bands like B, S& T at the time?

RB: Blood, Sweat & Tears was really organized. They had

a great arranger Freddie Lipsius, who was a wonderful jazz alto saxophonist. A

bebop player who had a band in New York and had a lot of great young players.

He could write and play his ass off. Maybe this was something that I shouldn’t

have heard because it was a big influence; we were walking down the street and

a fan came up to Fred and myself and asked “You guys are playing rock not jazz,

don’t you feel like you’re selling out?” and Freddie’s answer was “Look, I know

I can play, so I don’t have to prove it to anybody. This band features all my

writing and we get a chance to improvise. This band has a chance to really go

somewhere, rather than just playing in the New York clubs for five dollars a

night.” So he had a really good answer to that question, question that I was in

some ways asking myself, and it kind of influenced my thinking.

The thing about that band, it was all wonderful players,

Bobby Colomby on drums, Jimmy Fiedler on bass. They kind of set a standard for

rock playing because they were jazzers at heart, so they brought a jazz

mentality to the proceedings. That first B, S &T record Child is a Father to the Man is still a

classic record with some classic arrangements. I enjoyed myself playing in that

band, but I didn’t get a chance to improvise enough. Then Horace called. The

horn players were basically sidemen (in the first B, S & T), except for

Freddie, we got paid a salary. That was nice because we got paid whether we

worked or we didn’t. Several months into the band they had what was a classic

band meeting where they announced to Al Kooper-who was really instrumental in

starting the whole thing and adding horns to rock music ala Maynard Ferguson-they

decided without my knowing to add a new lead singer. They had found another

singer in Canada named David Clayton Thomas and they announced to Al that they

wanted him to stay in the band, but that they wanted Thomas to be the lead

singer. Al abruptly said I don’t want to do it and he quit. I had been talking

to Horace Silver and it was such a nice opportunity, a really great band with

Billy Cobham on drums (he had just come out of the Army), Bennie Maupin on saxophone

and John B. Williams. I just leapt at the chance, so I announced to the band

that I indeed was going to leave too. They begged me to stay and said they were

cutting in everyone equally going forward, we’re sharing things, we think we

can go far with this new lead singer. My response was “I don’t think you guys

will ever make it without Al.”

(Laughing) So I just walked out.

We left on good terms, they understood, they were all jazz fans.

I begged my friend Lew Soloff, who I met at a Joe Henderson

big band rehearsal the next day, to take my place. He was pretty anti-rock

music, which is kind of ironic. He really didn’t want to do it. He said “I

don’t want to play in a rock band, I want to play jazz.” By the end of the

rehearsal I talked him into it. I said “…look you get paid whether you play or

not,” I think they were paying one hundred dollars a week, “that’s two fifty-dollar

club dates that you don’t have to do.” So he begrudgingly said “ok, I’ll try

it.” So I feed him in, he met everybody, they had apparently asked at one point

previously to be lead trumpet. So he joined the band. They went out with David

Clayton Thomas and I went out with Horace making two fifty a week, which was

better than the hundred dollars a week I was making (with B, S '& T), but I

didn’t know Horace was going to take taxes out. I think I netted $147.50, out

of which I had to pay for my own hotel, which also didn’t know at the time.

Blood, Sweat & Tears went on to record their next record which had hits

like “Spinning Wheel” and “And When I Die” and went on to sell eleven million

records. So Soloff’s salary went to I think it was five thousand a week, which

in 1968 was like twenty thousand a week. We were taking trumpet lessons

together in New Jersey across the river. When we started doing that we would

take a bus out there together, eventually he started picking me up in a limo. (Laughter)

|

| Lew Soloff w Blood Sweat and Tears |

Years later, for about four or five years in a row the

original B, S'&T got together at the Bottom

Line with Al Kooper and we would do Child

is Father to the Man live and Lew and I played together there. We did it

until about the mid-nineties until it faded out. Interestingly enough, Stephen

King, the great writer, was in the band, he plays guitar and was friends with

Al.

NOJ: What gave you

the itch to get into fusion and start Dreams?

RB: I ended playing with Horace for about a year and a half.

We worked pretty extensively, we went to Europe and I became pretty close with

Billy Cobham in that band. One day we were out in California and another one of

those band meetings occurred. Horace called us all together and said guys I’m

taking a break and I’m breaking up the band, I’m giving you two weeks’ notice.

We were kind of mortified because we sounded great together and we wanted to

keep doing it. Billy and I trudged back to New York in mid-nineteen sixty-nine.

In the interim, my brother Michael had moved to New York and met a wonderful

trombone player named Barry Rodgers. Barry had a relationship with a pair of

singer/songwriters-Jeff Kent and Doug Lubahn. They were trying to start a band

and they were looking for a trumpet player and a drummer. So all of a sudden we

were back in town and I said to Mike, “I play trumpet and Billy plays drums?”

So we joined the band. In that situation it was a

great kind of James Brown, R'&B band. Jeff and Doug had some tunes that

really leant themselves to creative arranging. We got together and rehearsed

maybe five times a week and jammed up all the horn arrangements. It wasn’t like

B, S& T, we didn’t have formalized arrangements, there was a lot of

stretching out. It was kind of a collective horn improvisation, alá Mingus,

where we changed the parts a little every night. They kind of organically

developed. We rehearsed everything and by then cassettes had come out so we

could record all the rehearsals. So we would get together and listen to them a

decide what to keep and what to discard. We literally jammed up everything. It

was a great band, we got very popular in the New York area and became the house

band at the Village Gate.

|

| Randy and Michael Brecker in Dreams photo by Jeff Kent |

NOJ: Yeah that is where I first saw you guys. Wasn’t John

Abercrombie in that band?

|

| John Abercrombie photo by Jeff Kent |

|

| Billy Cobham w/Dreams |

RB: Yeah, at one point, we decided we needed a guitar. There

was only six of us and we decided we needed a guitar. We auditioned several

guys, I had met John some time before. I remember him coming over to my

apartment. I met him through a trombone player named Sam Burtis. He had just come to town.

He just had a charming way of playing rock with his wah-wah pedal. He wasn’t a

rock player and I don’t think he thought of himself as a rock player, but he

had a unique thing. Kind of humorous, played everything through his wah-wah

pedal. One day he couldn’t make rehearsal and we were playing through Barcus

Berry pick-ups and his wah-wah was sitting there and we had things called

Condors that could allow you to play through it to create sort of watery organ

sounds. So I patched my horn through Abercrombie’s wah-wah and man it sounded

great. So I started to use that. Miles would come to hear us play (at the Gate) and he would never say anything

and he would hear our horn effects, and this was right before Bitches Brew and I think we may have had

a little influence on him. He asked Billy to play on it, in fact Billy did play

on Bitches Brew, but somehow didn’t

get credit, but he is on there.

NOJ: Was Billy playing those clear Fibes drums that he used

when he went to Mahavishnu?

RB: No I don’t think so. He was just bulking up and adding

drum after drum and cymbal after cymbal. I remember I think Ginger Baker had an

influence on him. But he really set the standard back then. People hadn’t heard

a drummer that could play like that. When he left to join John McLaughlin’s Mahavishnu

Orchestra we had auditions to replace him (in Dreams), it was famous around New

York. We had drum auditions for about six months. We must have tried sixty or

seventy drummers trying to fill that spot and we finally just gave up and said

ok we couldn’t find a drummer that played like he did. Mike and I went back to

play with Horace. Billy really set the style.

One quick thing. Twenty years later with the return of the

Brecker Brothers Band in nineteen ninety-two we had the great drummer Dennis

Chambers. Low and behold a few months into it, John McLaughlin steals our

drummer again. He got Dennis for his group the Free Spirits. So here we go

again we had to have drum auditions, so we were reliving the dread at having to

find a drummer to replace Dennis. By this time this style was more prevalent

and we had six drummers that could all play great. It was almost impossible to

choose, but we wound up choosing Rodney Holmes, my great friend who had been

playing with me anyway and who also sounded great. But it’s just funny twenty

years later McLaughlin stole our drummer again.

NOJ: I was a big Mahavishnu fan. When I first heard them

they just floored me with their power, speed and virtuosity. I just thought they were amazing.

RB: That they were. I was a big fan, as mad as I was that

they stole Billy from us. John is a great guy and he has always been very

gracious to me and my wife when we go to the South of France. He is a wonderful

host.

NOJ: Dreams was by

all accounts a super group. Were there too many egos for the band to last or

was the chemistry just not there?

|

| The original band Dreams with Michael Brecker, Barry Rodgers, Doug Lubahn, Billy Cobham, Jeff Kent and Randy Brecker |

RB: After a while Doug and Jeff, who were great singers and

songwriters-their tunes lent themselves to our creative endeavors-but they

weren’t really improvisers. They couldn’t quite keep up, especially after we

added Abercrombie and we added a lead singer Eddie Vernon who could really belt

it out. It started to get tiring because we had to start backpedaling our

playing to keep in line with what they were doing. We ended up hiring the young Will Lee on bass

and Don Grolnick on keyboards and Chuck Rainey was on bass for a time. We all

became friends, but the main thing was we couldn’t find a drummer to replace

Billy and that’s what really destroyed the band.

NOJ: You and your brother Michael did a great deal of studio

work in the late sixties and seventies. How did you get into that groove and

who opened the doors for you in that way?

RB: We went into the

eighties and kind of into the nineties until it faded out and I really enjoyed

myself doing that. As I said, Marvin got me in to the studios in the sixties

when it was a suit and tie scene. I didn’t quite fit into that scene. David

Sanborn was involved in this too. He had come to New York and it was he,

myself, Michael, Barry Rodgers and Ronnie Cuber and we became known like a

section. We had a different thing going, we had an R & B inflection and

we’d fit into that scene, no suits. We

were younger and we had grown up with R & b and the Beatles so we kind of

fit into that scene more.

Dreams kind of helped us because a lot of New York

Contractors came down and heard us at the Gate

and that helped us get into the studio scene. We were the younger guys,

longer hair, no suits and ties and an R & B sensibility. Next thing you

know we were kind of in and a lot of older guys were out.

NOJ: Let’s talk about a landmark studio sessions that

were especially notable to me on of them Arif

Mardin’s Journey from 1974 and

Don Sebesky’s Giant Box from 1973.

Tell us about those sessions and what it was like to be in the studio with so

many kick ass musicians?

RB: It was a thrill, just to see how effortlessly they

operated. Intonation was always just perfect. They could sight read everything

and they just knew how to give the producer what they wanted. With Arif, he

liked what he heard and became a fan. I think we got the call for Journey through a violinist friend Gene

Orloff. Arif started calling us for all his sessions. I kind of became his

contractor because I was a little more responsible than some of the other guys.

So I would get a call every week saying Monday we need two trumpets, three

saxophones, two trombones and I would get the horn section together. Eventually

he started handing me things to write. So that was a great opportunity and just

a thrill.

Don Sebesky was just a great arranger. I did a couple of his

records. He did lot of stuff for CTI so I became close with him and his son. It

was just an exciting time, to be there every day. We worked every day, quite a

bit with the older cats until like Snooky moved to California, Bernie Glow,

unfortunately passed away at a relatively young age. I was just lucky to see

both worlds. I caught the tail end of the classic studio system with all those

guys, Mel Lewis, Thad Jones and it morphed into the jazz rock studio scene. I

remember those sessions clearly because it was early in on my studio career.

NOJ: You did a great album with guitarist Jack Wilkins in

1978 titled Merge (originally titled

The Jack Wilkins Quartet) with Jack De Johnette and Eddie Gomez. Was that a

working group or did you have plans to gig out of the studio?

RB: We were playing a lot together at Sweet Basil in that

configuration somehow. That session was really ‘live,’ it didn’t get started

till like midnight. I think after the gig; we went to a studio to record it

live with no overdubs. It was recorded in three or four hours. We did the whole

thing in one or two takes. It became one of my favorite records (The Jack Wilkins Quartet). A few years

later we added Mike to the band and I forget what it’s called (You Can’t Live Without It). Merge was released as like a combination

album from the two original albums.

NOJ: I read that you

formed the Brecker Brothers band at the insistence of the producer who felt the

name was a hook, originally this was supposed to be your solo album. Was this a

vehicle for your writing?

RB: The producer coined the name. We had been getting

together with guys from Dreams, we stayed friends, with no thought in mind of

forming a band. I had started to write. It’s funny how all this stuff is

connected, but Sanborn, who I had met at band camp, had moved down from Woodstock,

NY around 1973-74. Mike and I were playing with Billy. Grolnick was in town. Will

was floating around. We had become friendly with Steve Khan, who was living in

the same building with Will, drummer Chris Parker and Grolnick on Seventh

Avenue South, downtown. In my head I had wanted to do a solo record, so we

started rehearsing every week like a rehearsal band. Grolnick was writing some,

Steve Kahn was writing some and we were playing my horn charts. I had nine

charts together for those guys and I was going to do a demo with the intent of

doing a Randy Brecker record. It was a small world and word had gotten around

about the music and the rehearsals. Eventually I got a call from a guy, Steve Backer, who just

signed a production deal with Clive Davis who was just forming Arista records

and was looking to sign people. Clive had also signed Dreams to Columbia so we

knew him. The one caveat was that Clive wanted to call the band the Brecker

Brothers. He told me if I agreed we wouldn’t have to do a demo and we will sign

you to a record deal. I was upset, it was supposed to be my solo record. I had

been working really hard. Besides it was a three horn section and I thought

how’s that going to work? The Brecker Brothers? What about the other guy named

Sanborn on the front line, how’s that going to look? Is he going to be the lost

cousin or something?

|

| The Brecker Brothers Front Line 1975 photo by Erika Price David Sanborn, Michael Brecker, Randy Brecker & Steve Kahn |

They were insistent

and I thought about it for a week. I realized it was a great opportunity, after

all it was Clive Davis, and he was the best in the business, so I said ok. We

went in and recorded the nine tunes and it was an easy thing to do. I had put

the thing together and we went to a little studio owned by a rocker guy from

Philly, Todd Rundgren, called Secret Sound. We recorded the nine tunes, I

double tracked the horns, I knew all the tricks from having worked with B, S

& T. The producer was thrilled at how well prepared we were and how easily

we got all the tracks laid down. Great, the next day I get a call from Clive

Davis’ office requesting a meeting. So I go out alone to Clive’s office, the

other guys, Mike and Sanborn, couldn’t be less interested at the time about the

whole thing. So Clive said to me I love everything you did but we need a

single. I was frustrated and protested. “I’m already calling it the Brecker

Brothers it was supposed to be my solo album, now you want a single.” By the

end of the meeting it was apparent Clive wasn’t going to release the album

without a single. So I called everybody, we trudged back to the studio, it was as

I like to say the force was with us. We jammed up a tune like we used to do in

the Dreams days. Grolnick had a little idea, that’s what started it. We played

a lick and I still have the cassette. We recorded it in about four hours. Clive

came in towards the end of the session and he loved it. Thank God! It was a

tune called “Sneakin' up Behind You.” We stuck that on the record and it came

out, it was in the Average White Band mode, we were definitely influenced by

them. The single shot up to about number two I think on the R & B charts

and the record got up to about sixty on the top two hundred pop charts. Next

thing I know I had assumed it would sell maybe ten thousand records because it

was commercially oriented and it sold over two hundred thousand.

NOJ: Wow. And this was something you just whipped up for

Clive?

RB: Yeah, the single sold the

album. The album started selling and people thought we were African Americans,

the Brecker Brothers. It was like a hobby because we were all busy studio

musicians. We got six good records out of it back then and we tried to recreate

the hit on every single record but we could never repeat it.

NOJ: It’s hard. Those things are

like fleeting moments when a confluence of things just happen to the creative

spirit. Where did the jazz funk impetus come from?

RB: For me it came out of being in

Philly as a youngster and playing with blues bands, African American blues

bands, where guys jammed up all the parts. There was a band led by Mr. Blues in

Philly, he was a cop who played a lot of dances. That had a big influence,

there were no charts, there were maybe six or seven horns and everybody had to figure

out what to play. That had a big influence on the concept of Dreams and later,

more abstractly on the Brecker Brothers and everything we did.

Like I said playing with a lot of

organ trios. That was the birthplace of the B3 thing, so I did a lot of gigs

like that in Philly. Booker T learning all the Stax stuff when I was in school.

I loved the music. In Philly the jazz station was right next to the R &; B

station on the far end of the AM dial. Once I tuned in by chance and missed the

jazz station and heard James Brown and little Stevie Wonder when he was like

twelve or thirteen. Jimmy Forrest’s version of “Night Train” you know. I just

fell in love with that whole thing too.

NOJ: So there wasn’t any one band

that you can attribute to inspiring the funk/jazz sound of the Brecker Brothers?

RB: I guess James Brown and I have

to mention Parliament Fundadelic, they were tied in there too and their horn

writers. Dreams played a couple of shows opposite Parliament. They were called

Funkadelics, Mike told the story of how when we were playing on a tour opposite

Dreams and Mike sat on the bus with George Clinton. George heard Dreams and we

heard them and that was also a match made in heaven. We wound up playing on

some of the Parliament Funkadelic records. I met Fred Wesley and Pee Wee Ellis

and Maceo. We did sessions with them and Bernie Worrell, who we just lost, and

they were just great writers so I have to admit that was a big influence.

NOJ: You subsequently joined Jaco

Pastorius’ band. How did you meet and what drew you to him?

RB: We first heard of him through

the grapevine, you know you hear there is this great player down in Florida, Jaco.

I find this old date book from 1975 in an old drawer somewhere, and I saw this

session and I didn’t know how to spell his name so I wrote 2 – 5pm session with

Jocko. That session was produced by my old friend Bobby Colomby, who had a

studio in New City a little north of New York City. We played on a Sam and Dave

tune “Come on Come Over” and the rest of the horn section was Jaco’s guys from

Florida and that’s how we met him. At that session Herbie Hancock was there, he

wasn’t playing there but he was there. Jaco was amazing, you know his hands

were so huge and eventually he formed a band with Mike and Bob Mintzer. Mike

and Mintzer were close friends and he introduced Jaco to Mintzer, and they

played locally a lot, I think they played Seventh

Ave South if memory serves me and for Jaco’s birthday.

Truth of the matter is Mike went

into rehab in 1982 and Jaco needed someone to take his place so they called me

and I was thrilled to do it. Brecker Brothers had kind of closed their last

record deal. Mike came out of his treatment with flying colors. We were on a

tour so I ended up playing with Jaco and we did a bunch of tours together. The

only time I toured a lot in the states was with that band. It was myself, Mintzer, Jaco, Othello Molineaux,

Erskine and occasionally Don Alias. It was a great band.

NOJ: Didn’t you meet Eliane Elias

in that band?

RB: No not in that band. I met her through our club Seventh Avenue South. We owned Seventh Avenue South

and that band grew to fruition out of the club. Mike Mainieri put a band

together, Steps Ahead, originally with Mintzer, then Bob was starting his own big band. So

then it ended up being Mike, Mainieri, Steve Gadd, Eddie Gomez and Don Grolnick.

Then the second pianist was Eliane and we lived near each other. I would drop

her off after the gigs and eventually we became close and ended up getting

married for seven years. We are still

very close. She lives up the street from me. We have a daughter Amanda

together.

NOJ: You two formed your own band and Brazilian music became

part of your DNA. So much so you got your first Grammy for your album Into the Sun. What is it about Brazilian

music that captivated you?

RB: I think the melodies and the harmony, the sensibility

and the beautiful lyrics. I have a fondness and a love of Brazilian music way

before I met Eliane, although during our years together I would go to Brazil to

play with her and just stay with her family. My first trip to Brazil was in

1979 with the Mingus Dynasty. We were playing in Sao Paolo, but I made my way

to Rio with Ricardo Silveira, he actually plays on another of my Grammy

winning record called Randy in Brasil.

I just wound up staying there. I just fell in love with the place. Every day I

would say, amanhã, tomorrow I’ll go

home. I just stayed for two extra weeks.

I had been in love with Brazilian music ever since I was in

high school and heard an interview with Herbie Mann on the jazz station. They

played some stuff, he had just come back from Brazil and his mind had been

blown and he did a record in that style. Stan Getz had a hit with Astrud and

all that. So they were playing a lot of Brazilian stuff on the radio and I just

fell in love with it. So I started to research and getting some of the records and

just loved the melodies and the harmony and like I said the sensibility of the

whole thing. I am actually doing a tour starting in October and November going

to China and Europe with some of the guys from Randy in Brasil. The album won a Grammy probably ten years or so

ago. It’s with the Quartet Balaio. We’re doing some tunes off Randy in Brasil and touring China. I

haven’t been playing in that style for a while so it will be nice to get back

to that.

NOJ: What is your favorite solo, that you thought you really

crushed it on?

RB: That’s a tough one. Recent one’s that I like on Randy Pop on the first tune which is

Donald Fagen’s “New Frontier.” On this record we re-imagine hit tunes that I

have played on throughout my career. This was my wife Ada Rovatti’s idea. Kenny

Werner rearranged everything, my daughter Amanda sang, we had a great band. On

that song I played what I thought was a really great solo. It got reviewed in

Jazz Times magazine and the guy mentioned my solo, but I had some of my effects

on and he thought it was a synthesizer. So he credited it to Kenny Werner.

That’s a cool solo because there were no licks it was melodically oriented. It’s just for me a real

musical solo that doesn’t rely on clichés, so that one comes to mind. One that

is pretty well known is the solo on “Gregory is Here” from Horace Silver’s In Pursuit of the Twenty-Seventh Man

that’s a nice one from 1973 I think. There is some nice Michael Brecker solo

work on that one too.

NOJ: Two of my favorite solos are “Meeting Across the River”

from Bruce Springsteen’s Born to Run and

your Freddie Hubbard-like solo on Mark Murphy’s Red Clay.

RB: Thank you. I guess the Springsteen solo got a lot of

play. We recently did a Mark Murphy tribute at the Syracuse Jazz Festival with

the New York Voices. He was from Syracuse so his family was there so it was a

nice little tribute.

NOJ: Let’s talk about Lew Soloff. You two guys have seemed to have tracked a

parallel path at the same time. There’s the obvious B, S & T connection,

but both of you were first call studio musicians. I suspect you often were

called for the same gig at times?

|

| Lew Soloff |

RB: Yeah quite a bit. We did a lot of studio work together.

He was one of my closest friends and I miss him very much. One of the all-time

characters. He was one of the first trumpet players I had heard when I was

thinking of moving to New York. I had met the young drummer and later pianist

Barry Miles who was a child prodigy. I met him before I moved to New York and he

played me some tapes of his current band that had a trumpet player on the tape,

and I said to him “Who the heck is that playing trumpet?” That was Lew. I thought to myself, oh man I am going to

have to practice a lot before I get to New York in order to keep up with

everybody, because he sounded just great.

We first came face to face during the Duke Pearson big band.

Lew had just gotten out of the reserves and subbed in that band, so we became

best friends after that. He moved back to New York and we did a lot of playing

together. All the bands he subbed in Clark’s band, Duke Pearson’s band and Thad

and Mel’s band. He could also play lead so he did everything.

NOJ: What would you

say was Lew’s best attribute on the trumpet?

NOJ: Did Lew work in the studio as much as you did?

RB: Yeah maybe a little later. He had so much success with

B, S & T. They were out on the road a lot. In the early seventies they hit

it big. He bought a duplex on 52nd street and had it outrageously

furnished. I remember Alan Rubin and I questioned him because we thought the

lady designer he was using was taking advantage of him. I remember the two

floor duplex was designed as a Bedouin’s tent. (Laughter) He had a table that

was an elephant’s foot in his living room. Typical Lew. The latest stereo

equipment. I remember him looking for a record that he wanted to play for me at

his apartment and he was standing on it. He was just a wonderful heart, a

wonderful character.

NOJ: Do you have a favorite solo of his?

RB: Well the most

well-known solo is the one on “Spinning Wheel,” it is just such an indelible

part of that tune. Hopefully I won’t have to do it on this upcoming tribute

concert that we are doing in his memory. Because I can’t. In the Latin music world

Lew was it. Both Lew and I played together on some album, I can’t remember the

name but I think it had something to do with Beethoven. We each got to play on separate

cuts. This is a funny story. A guy called me up and said “You know this is the

greatest trumpet solo I have heard in your career. But it’s listed wrong on the

back of the record they have you listed as playing Lew’s solos and him listed

as playing on your solo.” So he sent me a copy of the record and I checked it

out and sure enough it wasn’t listed wrong. It was Lew’s great solos that he

was talking about. He was arguing with me that it had to be me, but it was

Lew’s solos. Lew just played his butt of on that thing.

NOJ: Gil Evans was a big influence on Lew, right?

RB: Yeah, as I told Lew, he should never be ashamed of that.

After Miles, Lew was Gil Evans’ trumpet player for years. He’s played on practically

all Gil Evans’ later recordings. At one point Lew did a re-take of Sketches of Spain and he was saying to

me how hard it is to do anything like that after Miles did it so beautifully. I

told him look Lew, after Miles you were Gil’s trumpet player so don’t malign

yourself, you did great. He just had a unique thing. His sound was completely

unique. His whole jazz conception was unique; you could spot Lew’s sound in two

seconds. He had so much command of the horn.

NOJ: In an interview he did before he passed, he seemed to

be in awe of some other player’s technique. I recall him being particularly in

awe of Jon Faddis’ technique. Do you agree with that assessment?

RB: That sounds like Lew. Everyone has their own identity,

that’s the thing. There is some stuff that Jon Faddis does that no one else can

do, but there is stuff that Lew could do that Jon can’t do, and there is stuff

that I can do that they both can’t do. What was so charming about our

relationship is that we were all such close friends. Occasionally Faddis would

get a part on a studio session that had a lot of articulation, a tonguing thing

and he would kind of surreptitiously hand it off to me or if I had a part that

had too many high notes I would pass it to him. Lew, out of all of us, could do

everything.

NOJ: You will be playing a tribute concert in his memory

with the NJCU Jazz Big Band with saxophonist Lou Marini on Sept 16th

at J. Owen Grundy Pier, Exchange Place, Jersey City NJ. Tell us how this came

about and what the source material you will be playing at this concert?

|

| Jon Faddis, Randy Brecker, Lew Soloff ,Dominic Degrasse and Alan Rubin photo from DominicDegrasse .com |

RB: It came about from Dick Lowenthal who teaches there. I

think he grew up in the same town as Lew, Lakewood,New Jersey. He put this

program together. He sent me some material that Lew could play and I hope I can

play it as well. We will be doing “Spinning Wheel,” some Lennon/McCartney, some

stuff Lew did when he was recording. Lew was very close with Maynard Ferguson,

played with him and was a big fan, so we will be doing a version of Maynard’s

“Fox Hunt.” We will also be doing an Oliver Nelson tune “Hoe-Down” and since we

both played in Frank Foster’s Octet, we’re doing a Frank Foster tune called

“Shell Game.” We doing songs that Lew had some sort of connection to in his

career.

NOJ: What’s next on you own agenda?

RB: There will be tours with the Brazilian Quartet, Quartet

Balaio. I will be traveling all over the world. September 8th I will

be doing a Phil Woods tribute in PA with my wife Ada Rovatti and others. Then I am going off

to the Ukraine for a weekend of Jazz on

the Dnieper and coming back and flying to Monterey Jazz Festival with Lew Tabackin.

Then I will be flying to Japan with Mike Mainieri and Bill Evans in a Steps

Ahead/SoulBop tour and then flying back and then flying to China so I’ll be

getting my frequent flyer miles. I’m trying not to think about it.

NOJ: How is your health? I read on your blog that you

recently went through a battery of procedures.

RB: Yeah everything is ok. So far so good.

NOJ: Thanks for spending the time to talk with us.