|

| Jack Wilkins, Billy Drummond, Harvie S and Sonny Fortune photo courtesy of Jack Wilkins |

We discussed Jack's biological father, who he didn't originally know and who was himself a fairly famous guitar player, in the last part of this interview. Jack thought a picture of his dad and one of his album covers from The River Boys might give a little insight into his innate musical heritage.

.jpeg) |

| Jack Rivers Lewis photo courtesy of Jack Wilkins |

Continuing our conversation:

JW: I have a new one coming out. It is not out yet. I recorded it in Paris and I like it a lot, which is difficult for me to say, because usually I don’t like anything I record. It’s true I don’t. I can’t listen to anything I record, I just hate it.

NOJ: One of the players that will be there for your

celebration is John Abercrombie. I am a big fan of John and his music. His is

one of my favorite players.

NOJ: What do you lies in the future for jazz guitar?

JW: Well, I have an interesting way of thinking about

that. A few years ago I asked my students what they were listening to. They

would tell me I’m listening to Coltrane, Miles Davis. I said wow, what phase of

Coltrane do you listen to? Because he

has had a lot of phases, you know and no

of them are the same. So they say to me “I

don’t know I have this compilation that I listen to. “OK, so what are some of

the tunes on that. “ Well they would tell me “ I don’t know.” That surprised

me. I said “You mean you listen to Coltrane and you don’t know the name of the

tune, you don’t know who is in the band?”

“Nah I just downloaded it.” Now I don’t think that is really learning

anything. You may like it but you’re not

‘going to remember it. I don’t think so. Maybe I am wrong about that. I don’t

even know. It’s such a complicated issue, downloading and all that wizardry that

goes on. It is so far out for a lot of people in my age group. If you are in

your twenties that is all you have, that is what you have grown up with.

JW: Well, I have an interesting way of thinking about

that. A few years ago I asked my students what they were listening to. They

would tell me I’m listening to Coltrane, Miles Davis. I said wow, what phase of

Coltrane do you listen to? Because he

has had a lot of phases, you know and no

of them are the same. So they say to me “I

don’t know I have this compilation that I listen to. “OK, so what are some of

the tunes on that. “ Well they would tell me “ I don’t know.” That surprised

me. I said “You mean you listen to Coltrane and you don’t know the name of the

tune, you don’t know who is in the band?”

“Nah I just downloaded it.” Now I don’t think that is really learning

anything. You may like it but you’re not

‘going to remember it. I don’t think so. Maybe I am wrong about that. I don’t

even know. It’s such a complicated issue, downloading and all that wizardry that

goes on. It is so far out for a lot of people in my age group. If you are in

your twenties that is all you have, that is what you have grown up with.

JW: That is a great thought. I don’t know about that but

that is very possible. The music was big band

with vocalists and they were around then after the war. The music is

still around today.

NOJ: What is your upcoming schedule for live performances

after the July 1, 2014 Jazz Standard date?

NOJ: You have played with some great singers over the

last forty years including Mel Torme, Sarah Vaughn, Chris Connor, Tony Bennett

etc. How does playing for a singer differ from playing with a group?

JW: It’s not that different. With a singer there is more

conscious dynamics and I think there are more conscious tempos too. Singer’s

always want a tempo that they want. You can’t play All the Things You Are for example fast or slow or any tune for

that matter, with a singer it has got to be in their tempo. I like playing with

singers, when they are good of course.

One of the singers that I really enjoyed playing for was Morgana King.

She was great. I loved her singing. Jay Clayton, Nancy Moreno, wow Sarah was wonderful;.

I liked them all. They all had something special.

One guy that I wished I had played for was Nat King Cole.

I played for his brother though, Freddy Cole.

|

| Sarah Vaughn |

NOJ: I did an interview with Freddy last year. He was

great.

JW: Ah what a nice cat and I loved the way he sang. Very

funny.

NOJ: He is very smooth. You know he never makes a set

list before a show. Poor Randy Napoleon, his musical director has to be

prepared for whatever he decides to play on the spot! He has an incredible

memory of all these tunes even at his age. I think he is now eighty two.

JW: Yeah I know I played with him. That’s what he did,

fortunately I knew the tunes. ( Laughter) He is terrific.

NOJ: Your teaching gigs include Manhattan School of

Music, Long Island University, the New School and NYU?

JW: Well I’m an adjunct to all of them. Manhattan was my

main school. There are not that many students at this point. I have plenty of

private students, sometimes more than I need. I can handle what I have so it is

not a burden. I like to teach.

NOJ: So what is it about teaching that you find most

satisfying?

JW: When I can hear somebody starting to play better

because of my helping them, I am very gratified about that. I am honored that

they got something from my teaching. I am very pleased about that, very

pleased. I want to help them because they so want to learn. Most of these

students want to learn that it gives me great pleasure to help them. They all usually have great attitudes and if

they don’t I won’t take them a second time. They respect what I do and they ask

me all the right questions and I am pretty honest. I don’t hold anything back. That would not be

helpful, if I said, that’s great see you next week.

They want the truth so I say your ‘comping is lousy, your

single line is a little sporadic, you’re not playing on the right changes, your

tone is shrill and your too loud. (Laughter) Your doing just fine.

NOJ: So go home now. (Laughter)

JW: Sometimes I’d

like to say that (Laughter) but seriously. With somebody so needy and so

wanting to learn you’re not going to hurt their feelings. You like them and you

want to help them.

NOJ: And you don’t

want to dampen their enthusiasm either, right?

JW: No. That is a very fine line.

NOJ: You have spoken in the past as to having learned

very early on to play within the music, within the group as opposed to

showcasing yourself on the bandstand. With the students you see coming up, is

there an emphasis today on chops more than musicality?

JW: Oh, totally, absolutely. It is sort of disturbing. It does not sit well

with me. They are not concerned about the music, they are not concerned about

playing the right changes, they’re not concerned about sound, and they are just

concerned about their chops. It’s preposterous! Who cares! There is always

somebody who can play faster. It is not about the speed, it’s about playing

with the music.

Speed is fine if it is organic. A lot times they practice these runs at home and they get on the bandstand and they play exactly the same thing. You can’t do that when you’re playing with a bass player and a drummer that are in the moment. You have to be in the moment when you play music. It’ll happen if you have a good band and they are all playing together, but I had that experience too. I was a kid, Mr. Hot Shot there, we have all done this. You get up there and you wail away and feel how fast and wonderful you are and then the next thing you know you’re there alone! That has happened to me, it was an incredible experience. The whole band stopped playing after a while, and I said why did you stop playing? They said “Oh we were listening to you.” A bell went off in my head. I wasn’t listening to them is what they were saying.

Speed is fine if it is organic. A lot times they practice these runs at home and they get on the bandstand and they play exactly the same thing. You can’t do that when you’re playing with a bass player and a drummer that are in the moment. You have to be in the moment when you play music. It’ll happen if you have a good band and they are all playing together, but I had that experience too. I was a kid, Mr. Hot Shot there, we have all done this. You get up there and you wail away and feel how fast and wonderful you are and then the next thing you know you’re there alone! That has happened to me, it was an incredible experience. The whole band stopped playing after a while, and I said why did you stop playing? They said “Oh we were listening to you.” A bell went off in my head. I wasn’t listening to them is what they were saying.

NOJ: You have several albums out. The latest one is Until It’s Time from 2008. Is that the last one or do you have a newer

one out?

JW: I have a new one coming out. It is not out yet. I recorded it in Paris and I like it a lot, which is difficult for me to say, because usually I don’t like anything I record. It’s true I don’t. I can’t listen to anything I record, I just hate it.

NOJ: Really, you are that critical of yourself?

JW: Not critical, it’s not that it isn’t good or okay or

whatever, it brings back too many memories of what I was feeling or going through at the time in

my life. What happens is it brings all the angst to the surface, again. That

was a moment in time. Music is like a portrait, you play something that you are

feeling at one time in your life, and then you put it on wax and it’s recorded

and it’s there forever. As soon as you hear again, maybe ten years later and you

go right back to that spot that you were in. You start reliving the past , you

know I didn’t like this or that was great but that part is gone, or

whatever. You know it is a real

introspective when you listen to your own music. That is why I am not keen on

listening to my own music.

NOJ: Tell me about

the new recording.

JW: Yeah, it was done in Paris. I have a trio, bass and

drums and we do a bunch of trio things plus we have a featured vibes player and

a harmonica player who is wonderful. I don’t have all the information but it is done. It is just being ordered and

mastered and it should be ready in a few weeks. I’ll send you one when it is

done.

NOJ: That would be great. You are now seventy and have been playing professionally for over

forty years. What advise do you have for aspiring musicians?

JW: That is a question that I am asked quite a lot. The

answer is to learn the fundamentals. Be on time if you have a gig, don’t be an

asshole.( Laughter) Learn as many tunes as you can, learn how to read. Develop

your ears so you can play a tune that you don’t

know. Be cooperative, don’t be

nasty. If you don’t like something just don’t do it, don’t do it with an

attitude. All you can do is hone your

professional skills, but therein lies

the problem. These kids don’t have a place to play anymore. There are not a lot

of venues. I was having some sessions here at my place for my students but it

turned out to be too much. There are places, Small’s has a jam session,

Cleopatra’s Needle, the Zinc Bar has a session a couple of places in Brooklyn.

NOJ: You Used to have a residency up on the Upper West

Side at an Italian joint called Bella Luna, but they don’t do that anymore,

right?

JW: No. We had a great run there seven or eight years.

NOJ: You had a lot

of great duos there.

JW: Oh the best. Bucky (Pizzarelli), Howard (Alden),

Freddie Bryant, Ron Jackson, Paul Meyers, Carl Barry the list goes on and on and on. It was fun

that place. Then they moved and the new place didn’t last that long. There are

places to play, but there are not as many as there used to be, and they not as

warm and cozy as they used to be.

NOJ: It must be

humbling to have had all the players that you had at your birthday bash show up

and want to honor you for your seventieth birthday celebration at the Jazz

Standard? ( The Jam Session Celebration was held to a pack house on July 1,

2014.)

JW: Oh of course, I am beyond flattered.

|

| Guitarist Jack Wilkins 70th Birthday Bash at the Jazz Standard w friends John Abercrombie, VIc Juris, Larry Coryell, Joe Diorio, Howard Alden and Jack |

JW: Me too, I love

John. A wonderful player and a wonderful cat too. One of my favorite records he

ever made was a record called Direct

Flight. It was with Peter Donald and George Mraz just a trio date while he was recording for ECM. People don’t

realize how straight ahead when he wants to.

NOJ: When musicians are in sync it is an incredible

experience and wonderful to behold.

You don’t always see that in performance. You said once

in another interview that you are very big on listening and I can understand

why, because if you don’t have the ears to listen to what the other players are

playing, where they are taking it, then how can you tell where the music can

possibly go?

JW: That is essential. That is almost elementary "1A" Be

in tune. Listening is to me the most important aspect of playing. John \(Abercrombie) told me a long time ago, John in his inimitable way said “Yeah, listening is my

meat and potatoes.” (Laughing loudly). Couldn’t

be more truthfully said.

NOJ: What do you lies in the future for jazz guitar?

JW: I think the economy is going to dictate where it

goes. Things can become obsolete if no body wants to buy it. That holds true

with just about everything. CDs are pretty much obsolete aren’t they?

NOJ: Well I like to get a lot of hard copy of what I review. I like the

packaging; reading about the artists;. how the music was made. Who wrote the

tunes etc.

JW: A lot of the kids today they just download it.

NOJ: Yeah they just download the music, but how connected

can you be to a digital download?

|

| John Coltrane and Miles Davis |

JW: Well, I have an interesting way of thinking about

that. A few years ago I asked my students what they were listening to. They

would tell me I’m listening to Coltrane, Miles Davis. I said wow, what phase of

Coltrane do you listen to? Because he

has had a lot of phases, you know and no

of them are the same. So they say to me “I

don’t know I have this compilation that I listen to. “OK, so what are some of

the tunes on that. “ Well they would tell me “ I don’t know.” That surprised

me. I said “You mean you listen to Coltrane and you don’t know the name of the

tune, you don’t know who is in the band?”

“Nah I just downloaded it.” Now I don’t think that is really learning

anything. You may like it but you’re not

‘going to remember it. I don’t think so. Maybe I am wrong about that. I don’t

even know. It’s such a complicated issue, downloading and all that wizardry that

goes on. It is so far out for a lot of people in my age group. If you are in

your twenties that is all you have, that is what you have grown up with.

JW: Well, I have an interesting way of thinking about

that. A few years ago I asked my students what they were listening to. They

would tell me I’m listening to Coltrane, Miles Davis. I said wow, what phase of

Coltrane do you listen to? Because he

has had a lot of phases, you know and no

of them are the same. So they say to me “I

don’t know I have this compilation that I listen to. “OK, so what are some of

the tunes on that. “ Well they would tell me “ I don’t know.” That surprised

me. I said “You mean you listen to Coltrane and you don’t know the name of the

tune, you don’t know who is in the band?”

“Nah I just downloaded it.” Now I don’t think that is really learning

anything. You may like it but you’re not

‘going to remember it. I don’t think so. Maybe I am wrong about that. I don’t

even know. It’s such a complicated issue, downloading and all that wizardry that

goes on. It is so far out for a lot of people in my age group. If you are in

your twenties that is all you have, that is what you have grown up with.

Students tell me “ I can’t remember tunes. I play a tune

three or four times and it doesn't stick with me.”

I tell them I am not surprised. You didn’t grow up with

this music. I did. When I was a kid, my step father and mother used to play

Billie Holiday, Frank Sinatra, Nat Cole

and I knew all these tunes. All

the great singers, I grew up with this music.

NOJ: If you never grew up with this music how can you

possibly embrace it. It goes back to heredity and environment. Environmental influences can be so powerful.

If you grow up exposed to something you are more likely to have an easier time

absorbing it and will most likely enjoy it.

JW: It’s true. Interestingly enough, students from Europe

and Japan are way more versed in the ( Great American Songbook) tunes then

American Students are.

NOJ: Isn’t that funny. I have a theory about that. The

Japanese have been very big jazz fans for decades and you wonder what it is

that drew them to this music. Maybe it was the GIs that were stationed there

after WWII during the reconstruction, listening to that music that laid the

groundwork for the Japanese people’s affinity for the music. The same could be

said for the American GI’s stationed in Europe during the Marshall Plan.

|

| GI's dancing to Big Band music with Japanese girls in Japan 1945 |

NOJ: Any new player that really impresses you these days.

JW: I can’t even say new but Adam Rodgers is quite

remarkable. I think he is just a brilliant, Jonathan Kriesberg, Ben Monder.

These guys are not even new are they? Like I said before, if you can play this

instrument at all in a good way, you get my vote right there, because I know

how hard it is to play this thing.

You know there are a lot of guitar players that I

mentioned, like Barney and Tal and Jimmy and the rest but I would be remiss if

I didn’t include Chuck Wayne in the pantheon of the greatest guitar players to

have ever played the guitar. The technique that Frank Gambale uses, Chuck Wayne

did that in the forties, of course Frank is playing different stuff, but Chuck

called it alternate consecutive picking. It is simple to fathom but different

to execute.

NOJ: Who is your most influential teacher?

JW: John Mehegan, pianist, and my early guitar teachers

Sid Margolis, Joe Monte and Rodrigo Riera, he was my classical guitar teacher.

He was amazing. I could never get that right flavor or feel for it.

NOJ: You live in

Manhattan and I understand that you are a SciFi fan. What is your favorite SciFi movie of all time?

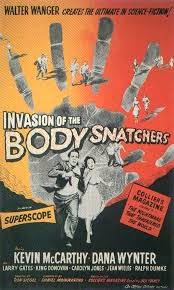

JW: How did you know that? I have several favorites. The Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Forbidden

Planet, the first Time Machine, Them.

My girlfriend thinks I am nuts. It

is very interesting that the way the world is going SciFi. In my apartment I have a big walk-in

closet with maybe five hundred movies. They are copies.

|

| The Original Invasion of the Body Snatchers |

JW: I am playing a duo with Carl Barry on July 26th at Grata Restaurant. On August 9th I am playing at the Bar Next

Door and at the Kitano on August 29th. Both gigs are with with Mike Clark on drums and Andy McKee on bass.

NOJ: I really appreciate your time and I look forward to

actually seeing you in person in the near future and hearing your new album.

You can hear link to Part 1 of this interview here and Part 2 of this interview here

You can hear link to Part 1 of this interview here and Part 2 of this interview here