Even if you are not a jazz fan, you have undoubtedly heard the deep, warm sound of Richard Davis' bass.

In the late sixties and into the seventies he worked as an in demand studio musician and was featured on landmark albums by some of the most identifiable artists of the time. He was on at least three albums by pop diva Barbara Streisand including My Name is Barbara (1965) and Color Me Barbara (1966). He was the bassist on Van Morrison's stream of consciousness album Astral Weeks (1968), he made an appearance on Paul Simon's There Goes Rhyming Simon (1973) and worked on three of Janis Ian's albums Stars ( 1974), Between the Lines (1975) and Aftertones (1976). He was the probing bottom sound on Bruce Springsteen's "Meeting Across the River" from Born to Run (1975). How many Bill Evans fans recall him as one of two bassists on the meeting of Stan Getz & Bill Evans from 1973? He worked with the jazz singers Sarah Vaughan(with whom he toured and recorded with on at least six of her albums), Chris Connor, Joe Williams and Etta Jones.Perhaps Davis' most impressive work was as a crucial contributing member of groups led by the more progressive musicians of the time including Eric Dolphy, Andrew Hill , Sun Ra, Elvin Jones and Rahsaan Roland Kirk.

Davis's bass was a sought after sound and he worked with a veritable who's who of saxophonists

including Ben Webster, Lucky Thompson, Sonny Stitt, Phil Woods, Joe Henderson, Lou Donaldson, Sam Rivers, Clifford Jordan, the aforementioned Dolphy and Kirk and the altoist/arranger Oliver Nelson to name just a few. His only regret is not getting to play with John Coltrane or Theolonius Monk, although Coltrane showed some interest in playing with him, but his friend Jimmy Garrison was already playing bass in the saxophonist's later quartet.

If that wasn't enough the classically trained bassist played in symphonic orchestras under the direction of Igor Stravinsky and Leonard Bernstein among others.

In this part two of my three part interview with Mr. Davis we explore the lineage and future of the bass in jazz, his career, the people he played with, his take on the classical bass and his impressions about teaching at the University of Wisconsin where he has been a professor of classical bass since 1977.

NOJ: To continue where we left off , in the pantheon of jazz bass players, is this list a

fair chronology of who you think evolved the bass through their own

innovations, from where it was in the early 1900's to where it is today? I’m thinking of Page, Stewart, Blanton, Pettiford, Brown,

LaFaro , Chambers, Ron Carter and yourself ? After that then

where is it going.

RD: I agree with what you said as far as the lineage

NOJ: And then who? Stanley Clarke, Marcus Miller and Victor

Wooten etc.

RD: Victor Wooten, Stanley Clarke and Marcus Miller, those

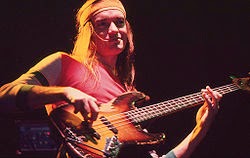

guys are playing crazy stuff. Don’t leave out Jaco Pastorious.

|

| Jaco Pastorius |

NOJ: Oh no, your right Jaco definitely deserves to be in

there. They are all so technically proficient and play with tremendous speed,

but sometimes I feel like they lack the poignancy that guys like you bring to

the bass. Can there be a joining of this high speed proficiency with

corresponding poignancy?

RD: I see. Well I’d rather leave that question alone.

NOJ: Let’s go back to your own musical chronology. You

started in Chicago and you were playing with the great Ahmad Jamal, when you

were switched spots with another bass player and summoned to New York to play

with Don Shirley in 1952 is that right?

RD: That is right.

NOJ: I read somewhere that Shirley also studied psychology

and that he did in the field experiments with his audience, checking to see if

his use of certain chord patterns or notes could elicit certain responses. Did

you experience that with him?

|

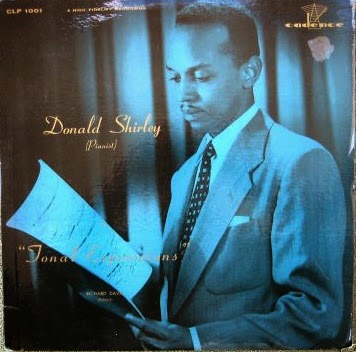

| Don Shirley Tonal Expressions 1955 |

From the Album liner notes on Don Shirley's Tonal Expressions 1955 by Al "JazzBo" Collins:

"One of the favored standards, "My Funny Valentine" receives especially good interpretation by Don Shirley with fine bowing by Richard Davis. He conveys more of the Pagliacci tragedy of this melody than we have ever heard before. The beauty and the sadness are real. The tonal effects are particularly effective here with the bowing laying a nice background for the piano notes to be dropped upon."

RD: This is the first time I am hearing about this.

NOJ: I read about Shirley and he apparently studied

psychology and was interested in the effects of certain musical chords on

people. I was wondering if you could shed some light on this information from

firsthand experience?

RD: I have no idea about that.

NOJ: I thought it was coincidental that you played with

Shirley and you also mentioned playing with Sunny Blount or Sun Ra, as he was

later called. You told a very funny story about playing with him one time at a

Calmut City burlesque house. He told you he could make a drunk in the audience

stand up and listen just by playing certain chords and then it proceeded to do

just that. It is sort of coincidental or

where these guys connected?

RD: I saw Sun Ra do this but I never saw Shirley do anything

like this. Sun Ra could do anything.

NOJ: Pretty wild. What was the most impressive thing about

Sun Ra?

RD; Highly spiritual, a world of wisdom and just a fantastic

musician.

NOJ: Do you think his music was too far out there for most

people to accept?

|

| Sonny Blount aka Sun Ra |

RD: No. He did in and

out. He did far out and far in.

NOJ: Did Don Shirley, who apparently composed classical

pieces, have any influence on you pursuing classical bass?

RD: No he did not have any influence on me, and I don’t know

about his composing classical pieces. He approached whatever pieces he was

playing, standards, in you might call it a euro-classical manner.I don’t know

anything about his composing. I stayed with him for three years. I don’t think

he had any influence on my playing, I just got an opportunity to play these

bass lines.

NOJ: Which classical Bassist did you most admire and why?

RD: Well the first bassist I heard on a recording was the

conductor of the Boston Symphony, his name

was Serge Koussevitzky. Fifteen years after he stopped playing the bass,

they asked him to do a recording. He consented to do the recording and I heard

about it in a magazine and I heard the recording and he plays three of his own

compositions.

NOJ: You have always maintained a dual identity as both a

jazz and a classical player. Do you think had the opportunities been more

forthcoming you would have preferred to have played Euro based classical music

for a profession?

RD: No I would have preferred to play jazz, but I can play

both and that is why I’m teaching now because I teach both.

NOJ: It’s pretty heartwarming to hear how well your students

appreciate your teaching and mentoring them at the University of Wisconsin

where you teach.

RD: Where did you see that?

NOJ: It’s pretty amazing what you can get off the internet

if you look, Richard.

RD: I developed a super program for young bassists around

the country. The Richard Davis Foundation for Young Bassists.

NOJ: That is pretty great. When you left Don Shirley you

went to the University of Sarah Vaughan. How was it different playing for Ms.

Vaughan?

RD: I had some intermittent gigs before that. I worked with

Charlie Ventura for a while and then the Sauter- Finnegan Band. Just some gigs

around New York and then I got the call to work with Sarah Vaughan

NOJ: Now how did you get the gig to work with Sarah?

RD: I don’t quite know, but I think the drummer Roy Haynes

might have had something to do with that. I’ve always wanted to ask him that

question, but I never remember to ask him, because he used to watch me play

with Ahmad Jamal. When he was in Chicago with Sarah Vaughan he would hang out. I

remember sitting at the bar with him when he would come out. So I imagine that

is my connection with Sarah Vaughan was through him.

NOJ: what was the most impressive thing about Ms Vaughn as a

musician that you learned playing with her for five years?

RD: First of all she had a keen sense of harmony. She had a

keen sense of improvisational skills on the harmony and she had a piano player

, Jimmy Jones, who knew how to play expressive harmony behind her.

NOJ The guitarist Jack Wilkins told me that accompanying a

singer is more about dynamics and pace than playing instrumentally with a band.

I have seen some film of you playing with Sarah and you look happy as hell. Did

you find playing with Vaughan a little restrictive after a while?

RD: Well it’s very true. With her you felt very comfortable

and free and relaxed because that is what she looked for. It’s fine until I

feel the need to move on. I just felt

eventually it was time to move on to do other things, because I couldn’t do it

with her, it wasn’t that kind of a group.

NOJ: Well I have listened to some of your later recordings and you certainly have done some interesting and different things with some cutting edge people. You were in New York and met Eric Dolphy on a subway

platform. He asked you if you were

playing Saturday and that was the beginning of a beautiful partnership. What

was so special about Eric and why do you think his music was so difficult for

the mainstream at the time?

RD: Why it was good for me is that he was playing things

that I could hear in my ear. That is what I was looking for when I got off the

road with Sarah Vaughan. I was looking for something that could satisfy my urge

to play with different chordal structures, different interpretations and he was

the answer. He was the answer.

NOJ: You guys played

together on Out to Lunch. In some respects your association with Eric was

like a parallel to the late Charlie Haden’s association with Ornette Coleman.

He was doing The Shape of Jazz to Come during that period and you guys were

doing Out to Lunch. What was going on with the music at this time? It was

like exploding in a different direction.

RD: It sure was. People still ask me about that recording.

NOJ: Not that music needs to be categorized, but what was

going on at that time to have moved the music in this direction? Were the musicians just searching for

something different?

RD: Well it could be on parallel with society at that time.

Society was looking for something different civil rights, freedom. James Brown

was singing a lot of things about “I’m Black and I’m Proud” and this thing was

not militant it was about love.

NOJ: It was a little radical.

RD: Some of the people that heard it like the militant Black

Panthers heard in a different way. Eric

was all about love. Eric Dolphy was all about love and so was James Brown. Eric

was all about love. James Brown was all about love. It was the sixties.

|

| Eric Dolphy |

NOJ: In that group you also had Tony Williams on drums,

Freddie Hubbard on Trumpet and Bobby Hutcherson on vibes? What was it like to

play with these guys especially young Williams?

RD: Like a dream come true.

NOJ: Did everyone look to Eric as a leader or was it a more

of cooperative effort?

RD: Well to be honest with you going back fifty years or so

it is difficult to go back and see that day, it is not easy.

NOJ: Was Eric a commanding presence?

RD: No he was just like one of the guts. Nothing like I’m

the leader or like that you know. It was his music. Most combo situations work

as a cooperative situation.

NOJ: You also played with Eric at the Five Spot Residency

with Mal Waldron on piano, Booker Ervin on trumpet and Ed Blackwell on drums.

How was this group different than the one that recorded for Blue Note?

RD: I don’t even recall Booker Ervin being on that job.

NOJ: You were also an instrumental part of Andrew Hill’s

“Point of Departure” recording in 1964 with Eric, Tony Williams, Kenny Dorham

and Joe Henderson. How was Hill’s music different from Dolphy’s previous outings?

RD: When I played with him I didn’t really realize that

Andrew was a genius at the time, he was just another musician. As a leader

Andrew had no leadership ego. He would just pass out the music and you would

play it, no whipping you into shape or anything like that.

NOJ: What was different about his approach?

RD: I don’t think he had an approach; he just left you alone

to do what you had to do.

NOJ: You went from touring Europe with Sarah Vaughan in 1958

where the music was all standrads to ten

years later veritably leading a very

loose almost wing it session on Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks album which was an

experiment in stream of consciousness lyrics and unstructured music. Did you

take what Morrison was doing at the time seriously or did you think it was just

another gig?

RD: The A&R people that produced that session were

people that I had worked with for a long time. They just told me that they were

having somebody coming in from Ireland or Scotland or somewhere and I had to

get together a group to do their thing.

NOJ: Were you expected to lead the musicians in the studio?

RD: I might have been expected to get the musicians together,

but like I said before no body had to lead these guys. We weren't even

introduced to Van Morrison. He came in sat in the booth and started to sing.

NOJ: You also did

some studio work for other very famous pop/rock albums of the ear. You played

on important albums by Janis Ian and Laura Nyro, Barbara Streisand, Frank

Sinatra, Paul Simon and Bruce Springsteen.

Where you specifically requested to play bass by these artists?

RD: Laura Nyro and Janis Ian must have asked for me. (For

Streisand)I was the bass player for arranger/conductor Peter Matz, who arranged

her first four or six albums, and he liked my bass. Bruce Springsteen had heard

my bass on the Van Morrison album and he said he wanted that bass player on his

album ( Davis played bass on “Meeting Across the River” from Springsteen’s

Born to Run album with trumpeter Randy

Brecker).

NOJ: You also played in symphony orchestras conducted by

Gunther Schuller, Igor Stravinsky and Leonard Bernstein to name a few. When you

play classical bass is there any room for artistic freedom or is the music

rigidly player?

RD: Just for your artistry on the instrument, but you are

really interpreting, taking your direction from the conductor. You have a

hundred people assembled so you take direction from the conductor who puts you

into focus. You have no individuality.

NOJ: You have been an educator at University of Wisconsin in

Madison since 1977. What made you leave New York?

RD: I just decided that I wanted to start teaching some

younger people what I had learned.

NOJ: How did you find Wisconsin?

RD: Cold.( Laughing)

NOJ: Were they receptive to you as a black educator in a

relatively predominantly white state?

RD: Wisconsin has a reputation for being a racial state. I

think eventually some people feared me because I was black. They thought I was

aloof, but I had to protect myself.. .Wisconsin is very racist.

NOJ: I take it you were a bit of a pioneer there?

RD: What do mean by a pioneer?

NOJ: Somebody that went ahead of other people and blazed the

way. I take it by now there is much more diversity and integration in the

school system?

RD: It’s still the same, nothing has changed.

NOJ: Well, that’s disheartening.

RD: I’m still working on diversity. I have some allies. I

have lots of allies and I have a lot of people who don’t even realize that it

exists there.

|

| Educator Professor Davis a U of W |

NOJ: Has affirmative action helped Wisconsin integrate more

people of color into the educational system?

RD: When you look at the numbers there is still three

percent Black and 8 % people of color and I don’t know what they are doing

about that.

NOJ: You are an avid horseman your whole life. How does the

rhythm of riding relate to the rhythms of music?

RD: Well rhythm, tempo and pacing is part of riding the

horse. You have rhythm in the horse, there is tempo in a horse and a certain

gait of space and how you are going to cover that space , especially when you

are jumping with a horse. I was just watching some old video when you called.

NOJ You have been on over three thousand recordings in

almost all genres of music. Is there a particular soft spot in your heart for

any particular type of music?

RD: Jazz is closest to my heart.

NOJ: Your last album was in 2008. What album are you most

proud of and why?

Rd: I guess the album I am most proud of was Philosophy of the Spiritual ( from 1971). The

way that Bill Lee assembled that, he made the arrangements and he always

thought I had a specific bow technique and he utilized that and I had a chance

to play all those beautiful melodies, I remember "Dear Old Stockholm," Bill saw

that and he emphasized that and made the arrangements for that.

NOJ: In the nineteen sixties do you think you took a

militant stance against racism?

RD: No I didn't take a militant stance, because militancy

defeats the purpose. I didn't take any particular stance, I just thought it was

something that I didn't like. I didn't go parading around.

NOJ: In the jazz music world what white musicians did you

feel were blind to color?

RD: Benny Goodman was one, Stan Getz was one, Dave Brubeck

was one. Of course Duke Ellington was like a social worker.

NOJ: As an active

educator you must be current on the contemporary bass players out there. Does

anyone in particular seem to be holding the mantle of jazz bass a little bit

higher?

RD: Yeah, Christian McBride, Kenny Davis and I can’t think of anyone else right now, oh Esperanza Spalding.

NOJ: There are more and more women playing bass these days. Besides Esperanza there is Linda Oh, Tal Wilkenfeld, Iris Ornig and Meshell Ndegeocello to name a few.

RD: That’s good!

|

| Bassist Esperanza Spalding |

NOJ: I am sure you have taught some really incredible female bass players. With the continuously shrinking audiences for both jazz and classical music ,do you think it is going to be able to survive in this age where everything is so quickly changing?

RD: I certainly hope it survives, but who is to know? I don’t know.

NOJ: With such a paucity of venues for upcoming musicians to

play at, what is your advice for those musicians who want to make the music

their life?

RD: Well my teacher told me to get a degree in education. If

the gigs aren't there you can always teach.

To read part one of this interview click

here. Part three of this interview will be more on Mr. Davis' views on education and race relations in this country.